In the last blog posted, I shared the responses that Brazil’s COP30 Presidency provided to questions I sent them as part of my Master’s research. These questions aimed to better understand how Brazil is navigating significant contradictions in its climate strategy regarding agribusiness, oil, and Indigenous peoples on the path to the Amazon climate summit.

In many respects, this is a journey that began at COP27, when President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva declared that ‘Brazil is back’ in the fight against climate change. Through the COP30 Presidency, the Lula government claims to be offering a new vision of development for Brazil and the Global South, one that is based on social justice and protecting the forest.

My master’s research at the University of Leeds explores Brazil’s unique approach to climate leadership, dealing with the obstacles presented by agribusiness and the temptation to expand its oil exploration. To understand the official strategy for managing these critical issues, my research obtained direct responses from the COP30 Presidency. The analysis uncovers a unique operation of public diplomacy, based on recognition, reframing, and the discursive management of its paradoxes.

1. The Agribusiness: A Strategy of Dialogue and Differentiation

The first question addresses the dilemma of agribusiness, a pillar of the Brazilian economy and, at the same time, the main historical driver of deforestation. How does the COP30 presidency plan to engage this sector?

The official response focuses on a strategy of dialogue and differentiation. The Presidency stated that its goal is to “foster dialogue with all segments of agribusiness,” seeking to “reconcile economic growth with climate goals” and, crucially, “highlighting family farming as a constructive example.”

The current political agenda that views forests as obstacles to development, with the agricultural business that creates laws such as the PL da devastação (devastation bill), which grants authority for companies to do anything to the environment without following any environmental policy.

Instead of confronting agribusiness as a monolithic block, the strategy seeks to fracture it: to engage in dialogue with the “modern” and export-oriented faction, for whom sustainability is a matter of competitiveness, while elevating family farming as the virtuous model to be followed. This appears to be an attempt to build a coalition for sustainability from within the agricultural sector itself. The challenge, however, is that the Bancada Ruralista (Ruralist Caucus) in Congress, which represents the more expansionist interests, still holds disproportionate political power. The dialogue strategy, although necessary, still needs to prove that it can overcome the structural forces driving deforestation.

2. Oil: The Narrative of Sovereignty and the “Just Transition”

The sharpest paradox is the apparent contradiction between hosting the “Amazon COP” and the potential expansion of the oil frontier in the Amazon River Delta. At the moment, Brazil is selling off petrol lots in the country (Arayara image of the selling petrol).

How does the presidency manage this tension? The response appeals to national sovereignty and the pragmatism of the Paris Agreement. The Presidency “acknowledges the concerns” but emphasises that, under the Agreement, “each country defines its path for the gradual phase-out of fossil fuels according to its economic realities. ” The transition, according to them, “is a gradual process, shaped by national contexts and financing challenges.”

This argument is a classic defence of the Global South, seeking to position Brazil alongside other developing nations facing similar dilemmas, “if they [the Global North] had the chance to explore and develop, we have it too”. The strategy is to reframe what critics see as hypocrisy into the necessity of a “just transition.” However, this narrative clashes with the scientific urgency of drastic emission cuts this decade to keep the 1.5°C goal alive. The stance, although diplomatically defensible, undermines Brazil’s moral authority to demand more ambition from others, especially from fossil fuel producers in the Global North, revealing the intrinsic difficulty of reconciling the need for export revenues with global climate leadership.

3. Indigenous Peoples: The Symbolic Centrality and the Challenge of Effectiveness Participation of Indigenous People

The official discourse places Iindigenous peoples at the centre of the climate solution. However, how can we ensure that this participation is effective and not merely symbolic? In Brazil, Iindigenous lands are the areas that are preserved today, spanning from north to south, and are characterised by being surrounded by deforestation.

The Presidency’s approach to expand Indigenous participation at COP30 is to create platforms and to amplify voices. The key initiative is the creation of a “COP Village” at the Federal University of Pará, designed to host 3,000 Indigenous participants — a substantial increase from previous COPs. The goal is to create a space to “integrate their knowledge” and “strengthen their influence” in decisions about the future of the Amazon.

This is a powerful and visible act of public diplomacy. It directly responds to the demand for greater inclusion and recognition. However, critical analysis should question whether “amplifying voices” translates into real decision-making power. As detailed in my research, the most serious threat to Indigenous peoples is not the lack of a microphone, but the invasion of their lands by miners and loggers, and the pressure from agribusiness. The solution offered by the Presidency addresses the symptom of international invisibility but remains silent on how the Brazilian State intends to resolve the structural causes of violence and expropriation. The leadership, in this case, runs the risk of becoming performative: a celebration of indigenous culture on the COP stage, disconnected from the daily struggle for survival in their territories.

4. Amazon flying rivers and tipping points

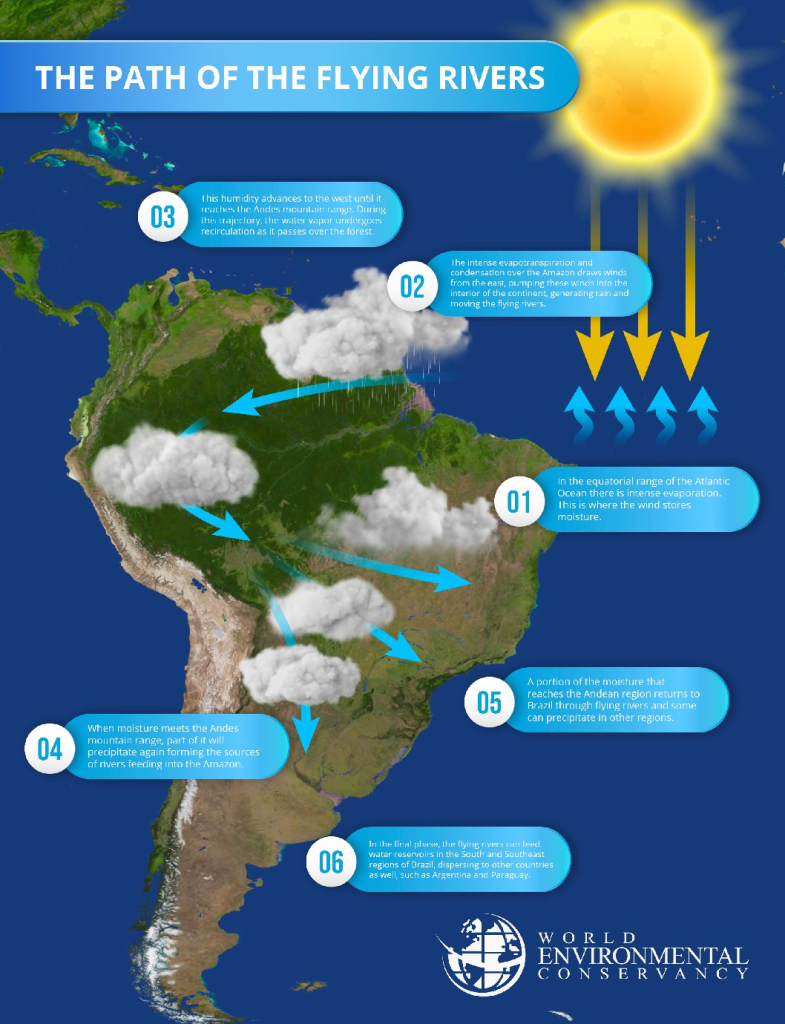

As we analyse Brazil’s complex strategy for COP30, with its dilemmas between agribusiness and conservation, oil and climate leadership, and discourse versus practice regarding Indigenous peoples, it is easy to get lost in the politics of climate diplomacy. However, in the end, what is at stake in Belém transcends diplomacy. The battle for the future of the Amazon is a battle for our own survival, and science reveals two frightening and urgent concepts: the tipping point and the flying rivers. A tipping point is a limit beyond which the damage becomes irreversible. Scientists, like Thomas Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, warn that if accumulated deforestation in the Amazon exceeds 20 to 25%, the forest could undergo a cascading collapse, ceasing to produce rain and transforming into a dry savanna (Nature, 2020; 2022). This is not a distant possibility; it is an imminent risk. Every hectare burnt to make way for pasture or every oil well drilled in a sensitive area pushes us closer to this abyss.

Why does it matter if we lose the Amazon? Beyond the homes of the people who live and depend on the forest, there is also the issue of the flying rivers. The Amazon is the climate infrastructure that sustains a large part of South America. Every day, it pumps a greater volume of water vapour into the atmosphere than the discharge of the Amazon River itself. These “rivers in the sky” transport the rain that irrigates the crops in Brazil’s Midwest, fill the water reservoirs of São Paulo and Buenos Aires, and power the hydroelectric dams that generate our energy. Reaching a tipping point would mean turning off this water source.

Therefore, COP30 in Belém is not just about Brazil, nor just about the Amazon. It is about recognising that the economy and ecology are not opposing forces, but a single interconnected system. The protection offered by Indigenous peoples is not an act of charity, but an essential ecosystem service. The unchecked expansion of agribusiness poses not only an environmental problem but also long-term economic self-sabotage.

The real question that COP30 forces us to face is this: are we willing to sacrifice the climatic and water stability of a continent for short-term gains? The Amazon is presenting us with a critical decision. What we decide in Belém, and more importantly, what we do afterwards, will define whether we heed the warning and act in time.

Conclusion: Brazil’s Leadership – A Complex Interplay of Factors

The Presidency’s responses to the questions I asked, reveals a coherent strategy of discursive management. The Presidency of COP30 does not deny its paradoxes but reframes them as complex challenges of a developing nation, and offers a global vision of the future based on inclusion and justice. My research concludes that Brazil’s leadership is, therefore, conditional. COP30 offers an unprecedented platform that advances its ambition, but the same event undermines that ambition by exposing the gap between rhetoric and reality. This leadership will not be judged by the beauty of this narrative, but by the ability to translate it into concrete actions that begin to resolve, not just manage, these profound and challenging paradoxes. Only time will allow us to judge whether COP30 and Brazil are successful or not.

Read More – COP30 will include food..